The Art Newspaper reports today that figures from the Golden Gateway of Taleju Bhawani Temple at Patan Durbar Square have been withdrawn from auction (Catherine Hickley, “Bonhams consignor withdraws looted Nepalese sculptures from auction”4th June 2021). The lost images were replaced in 2012 based on photographs taken much earlier (see earlier blog post Preservation of metalwork: Patan Royal Palace). Hopefully this provides an opportunity for the icons to return home to Nepal!

19th ICOM-CC Triennial Conference

The ICOM-CC Triennial Conference, planned to take place last fall in Beijing, China, is being held in virtual format this week under the theme “Transcending Boundaries: Integrated Approaches to Conservation”. The Conservation Committee of ICOM contains 21 working groups, which are presenting in parallel sessions, with a particular focus on global perspectives and inclusive conservation approaches. Participants can view recorded videos, and download papers and posters until June 17, 2021, from the virtual platform.

https://virtualconference.icom-cc2020beijing.com/

Our research on the preservation of metalwork in Nepal was presented and published in the Metal working group.

Renovation of the Tashi Gomang chaitya of Svayambhu

Time passes and work in Nepal continues with interesting results.

Nutan Sharma, who has been my research partner in Nepal, recently produced a fascinating documentary video on the renovation of Tashi Gomang chaitya of Svayambhu for UNESCO. Tibetans call it “the stupa with many auspicious openings” due to the many doors holding images in its outer wall. The small chaitya was badly damaged in the 2015 earthquake and, as a result, had to be excavated and rebuilt. Prior to the work, the chaitya divinity had to be appeased and was transferred into a holy vessel. After completion of the renovation it was reinstated with a special ceremony.

During the excavation, a large amount of foundation deposits were discovered. As is customary in Nepal, dedications had been interred within the building. Next to innumerable tiny mud stupas, also valuable metal objects, coins, and icons were recovered. After documentation, they were reburied during the reconstruction of the new building.

The project was carried out in collaboration of UNESCO, the Department of Archaeology, and The Federation of Svayambhu Management and Conservation, and was supported many other entities and individuals.

Presentation at the 46 Annual Meeting of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) May 30, 2018, Houston, TX

The Annual Meeting of AIC is hosting a pre-session symposium on Wednesday, May 30, 2018, under the title “Whose Cultural Heritage? Whose Conservation Strategy?”. During this program I will present a brief introduction of my studies in Nepal in a talk “Metalwork in the Kathmandu Valley: Melding of Reverence and Preservation”.

The full program of the symposium can be found at:

Click to access am2018-cultural-heritage-symposium.pdf

News from Nepal via My Republica, April 1, 2017: “KVPT puts back Yognarendra’s statue on pedestal”

Earlier this week, a group of gilded copper sculptures depicting King Yognarendra Malla and his two queens were returned to the top of their stone pillar at the Durbar Square of Patan by the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT). The sculptures toppled during the 2015 earthquake and suffered severe structural damage.

Rohit Ranjeetkar from KVPT very kindly allowed me to view the damaged sculptures up close in storage during my stay in Nepal one year ago. Despite their then partially ripped, crushed and dusty condition, the artistry of the repoussé work and thick surface gilding was still breathtaking: beautifully modeled faces, intricate surface decoration suggesting rich fabrics, and small movable pieces of jewelry. I look forward to learning more about the treatment that brought them back into their glory. Amazing work done in a short timeframe. Congratulations!

http://www.myrepublica.com/news/15596/

Text: Gyan Neupane, Pictures: Dipesh Shrestha

Picture: Dipesh Shrestha (from My Republica article)

Picture: Dipesh Shrestha (from My Republica article)

PBS Newshour on Nepal’s cultural heritage

On June 1st, 2016, PBS Newshour’s Culture at Risk series focused on Nepal’s culture heritage and repairs in the aftermath of the 2015 earthquake.

Special corresponded Fred de Sam Lazaro interviewed Christian Manhart, UNESCO and Rohit Ranjitkar, Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust, and Shukra Sagar Shresta, Archaeologist.

Below a thought provoking quote from the interview, which also includes wonderful video from Patan and ongoing work:

“FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Rohit Ranjitkar is with a nonprofit organization called the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust. He says, for most Nepalis, these historic sites are first and foremost places of active worship.

ROHIT RANJITKAR: Basically, they have the attachment with the God and the place with the religious activities, not with the architecture. You know, for them, the temple will be rebuilt or not rebuilt. It does not make any difference.”

Puja – offerings

Time has passed all too quickly. I will leave Nepal today, and carry with me wonderful experiences, new insights and knowledge, and new friendships!

With deepest thanks and appreciations to everyone who took time to meet with me and answer endless questions, to allow me to watch their work, take images, and showcase them here.

And to the kind people here, and elsewhere, who supported me in many ways – and to the institutions who made my time and research during the last month possible!

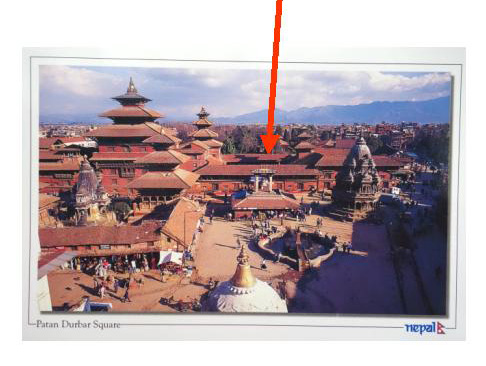

Preservation of metalwork: Patan Royal Palace

Patan is one of the three royal cities in Nepal, perhaps the oldest, and the Durbar Square in its center is one of the country’s seven World Heritage Sites. Since its inscription into the UNESCO list, extensive preservation projects have been carried out, in particular on the Royal Palace, which was erected by the Malla kings in the mid 17th century. Of special importance for the narrative of this blog is the recent conservation of the extraordinary metal doors and ornaments inside one of the palace courtyards (Mul Chowk), the private residence of the Mallas. The entrance wall to the private royal tantric Taleju shrine was embellished with a gilded repoussé doorframe and torana (tympanon). On each side of it, mounted onto the brick wall, were life-size gilded images of the rivers Ganga (to the left) and Yamuna (to the right). Comparable walls can be found in Taleju temple, Bhakatpur, and Hanuman Dhoka, Kathmandu, but they are not accessible to visitors at the moment. The Patan assemblage dates back to the 17th century in its earlier parts, although many additions may have been added later.

The entrance wall to the private royal tantric Taleju shrine was embellished with a gilded repoussé doorframe and torana (tympanon). On each side of it, mounted onto the brick wall, were life-size gilded images of the rivers Ganga (to the left) and Yamuna (to the right). Comparable walls can be found in Taleju temple, Bhakatpur, and Hanuman Dhoka, Kathmandu, but they are not accessible to visitors at the moment. The Patan assemblage dates back to the 17th century in its earlier parts, although many additions may have been added later.

Over time, extensive damage occurred, in part due to theft, and likely even caused by vandalism. The torana had suffered losses of 12 three-dimensional figures in the 1970s. Much of the metalwork needed to be cleaned, some parts required reforming of dents and other damage, filling of losses, and the large figures were in need of new backgrounds and support. The conservation concept was developed and executed by conservators from the University of Applied Arts, Vienna, together with Patan metal craftsmen. Based on photographs taken by Mary Slusser prior to losses at the torana, for example, these images were recreated by the lost wax method by a local artisan. The combination of current conservation methods in conjunction with traditional crafts, very similar to those used in the original creation of the various elements over time, led to impressive results!

The small Yantaju shrine in the center of the courtyard, dedicated to a personal deity of Malla kings, is another spectacular example of recent repair. Based on drawings, lost decorative plaques were replicated. Original versus new elements are easily detectable by different hues of gilding.

Recent work on the finial for the tantric Taleju shrine:

During my month in Nepal, I returned to the Royal Palace frequently and was able to witness how the work on one of the finials progressed quickly (see entry of April 1, 2016). Misshaped metal was straightened, supported and assembled, and a new tip was worked in repoussé from copper sheet by a Patan master craftsman. Viewing this work in progress allowed a glimpse into the much more complicated treatment of the Golden Doorway!

Credits:

Sincere thanks to Thomas Schrom for sharing recollections and documentation on the project. Also to Rohit Ranjitkar, Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT) for discussions, allowing me to view the work on the pinnacle, and to glance into storage where earthquake damaged sculptures await their treatment. Apart from the sadness of this situation – what a treat to see such artwork close up!

The treatments of the door and two river sculptures in Mul Chowk were been carried out in collaboration with the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT) and the Conservation Department of the University of Applied Arts, Vienna.

For further information please visit the KVPT website:

Reflections on preservation. Part 2: Kumbeshwar Mahadev Mandir

During the ‘second’ earthquake on May 12, 2015 (this is the way last year’s quakes are referred to in Nepal), the large copper finial of the five-tiered pagoda of the Kumbeshwar temple came crashing down into its courtyard. The recollections of the temple priest, Madha Shyam Sharma, are still vivid. Of this particular event, and how he carried the finial into the sanctuary for safety. And of course, of April 25 last year, when he experienced the first earthquake inside the temple.

Dedicated to Siva, it is one of the oldest temples in Patan, and, like many others, was destroyed in the 1934 earthquake and since rebuilt. While the temple did not collapse or show major cracks sine 2015, surveys identified the upper tiers as potentially unstable (notice the lacking finial below). The finial is now in storage with the Department of Archaeology for safekeeping, as temples are property of the government. Awaiting treatment.

The precincts also contain an important shrine of the goddess Bagalamukhli, a manifestation of Kali. This smaller temple was more recently destroyed by fire in 1997, and subsequently renewed (it survived the 2015 quake well). Puja (offering) at this shrine is considered wish-fulfilling and it can become very busy here at times! In the offering, terra-cotta dishes filled with 125,000 cotton wicks are lit inside the temple and carried outside in front of it. The intense smoke has created thick layers of soot and patina on the newly installed metal doorframes, which are partially cleaned where rubbed and touched.

The small, silver-clad small shrine housing the deity’s image, created by one of the master craftsmen from the extended Shakya family in 1931, was not replaced after the 1997 renovation. The small heads of deities showed holes due to repeated rubbing. Thus, a new silver shrine was commissioned – of slightly different design (see above). For newly installed metal items, a special ceremony needs to be followed, an “establishment puja” that fully activates the new work.

The silver of the old shrine was meant to be reused, perhaps melted down. By good fortune it found its way into the Patan Museum, where the recent photographs, seen above, were taken. Holes in the heads of gods and all. It is said to contain a bottomless pit, suggested there by a mirror.

The earthquakes, fire damage, a dislocated finial in official storage and a discarded shrine now on display in a museum – much food for thought!

Reflections on preservation. Part 1: Oku-Bahal

Multi-layered may be the word that describes best the situation one encounters with Nepal’s rich cultural heritage. Complexity, of course, is not unique to Nepal, but perhaps things are just a bit more so here? Palaces, temples, shrines and other structures have been renovated, enlarged, enriched, and also rebuilt after fires and earthquakes over centuries. They are being rebuilt, and not just after 2015. Many of the sites that visitors come from afar to marvel at are integral to a living culture, are part of festivals, processions, and performances. There is not much, or nothing, that is “parkified”!

Yet, responsibility for upkeep has traditionally been deeply anchored in Newari society and has been in the hands of guthis, or local trusts. Such community based-groups have been responsible for the maintenance of religious as well as public structures and monuments.

The reverence for the old and, perhaps, the original, however, may be viewed differently when compared to a Western point of view. For example, an icon that suffered fatal damage, such as a break across a stone sculpture, would loose its spiritual power. Repair (even if carried out with greatest finesse) could not reverse that. Yet, many important images of deities also are being resurfaced and repainted on a regular basis. During worship they are dressed and adorned. Their original materials and construction are rarely seen and remain often unknown.

In ongoing renewal and rebuilding activities, old was substituted by new – and old metal was often remelted and recast. Additions and repairs to shrines, as often, have been and are frequently donor driven. Thus, remaking has a long tradition and the crafts are still much alive.

The monastery of Oku-Bahal has a particularly close relationship with the metal images makers and artisans that live in its surroundings. A committee of the monastery has been responsible for selecting the appropriate craftsman for repairs, and there is the Rudruvarma Mahavir Preservation Committee that oversees such efforts.

The main icon worshipped in this sanctuary, in addition to others that can be glimpsed in the photographs, suffered damage during the 2015 earthquake and remains covered under white drapery.

Its body is surfaced with clay, which cracked. A patchwork of condition photographs is mounted inside the courtyard of the monastery and a banner asks for donations for its repair. Also losses to its gilt copper repoussé back screen are being filled.